Katarzyna Szota-Eksner runs a blog on Pyskowice and collects herstories that she is able to discover. Some of them has been also published in a book. She inspires others to look for non-obvious tropes and inspiring characters.

Pyskowice is a small town in southern Poland. Like in every Polish city, most of its streets or squares are named after male heroes. I am standing in a small market square, it is a warm summer afternoon. I am looking at the town houses, the beautiful, restored Town Hall and the Ratuszowa (Town Hall) Restaurant, already out of business.

I am thinking of the women who were here before me.

(Where did all the women who were here before us go, and why do we know so little about them? How many famous women do you know? And female street names? Why is bravery a male quality and why should ‘women’s talk’ be futile and frivolous? And what about power? Do we know any female warriors and soldiers?)

Will I meet a woman from Pyskowice?

I am therefore embarking on a herstorical journey (herstory is a neologism created in opposition to ‘his-story’, which has already functioned as a recognizable formula of scientific jargon and popular language for over twenty years).

There is a thriving group of amateur historians in Pyskowice. They are all willing to help. However, the beginnings are difficult – there have been many noble male residents in the past but women’s stories are scarce. Roland Skubała, a lover of Silesian and Pyskowice history, the owner and creator of the historical-military museum, comes to help. And so I learn the moving story of his grandmother, a Pyskowice resident – Helena, who was driven out of her beloved town by the Second World War.

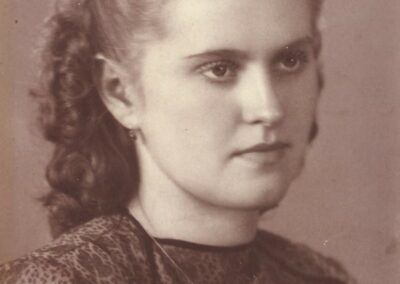

In 1944, she is seventeen. She is sent by the Employment Office to work in the Brickyard (the headquarters of the anti-aircraft defence at the time). As a telephone operator, Helena distributes reports. When it is clear that the Russians are approaching Pyskowice, one of the officers persuades her to stay with her family, but she decides to go with the army deep into Germany. On the way she survives the bombing of Dresden.

“You had to lie face down in the snow. The Allies dropped phosphorus bombs that started fires, very difficult to put out. I survived!” years later she tells her grandson.

Together with other like her, the young girl escapes from the destroyed city across the Elbe river. The Russians are following closely on their heels.

(I can’t help but want to hear more stories, and the Pyskowice herstory resounds more and more boldly).

…

A spring rain is falling. I am standing in front of the Pyskowice secondary school building. The beautiful red brick building in the Gothic-Romanesque style was put into use in 1861. In 1945 it started to host a secondary school and a junior high-school. The education lasted six years, including four years of junior high school and two years of secondary school. At the beginnig, there were no Polish books or many teaching aids and the building needed further renovation.

Currently, the building also houses a Psychological and Pedagogical Clinic. I have an appointment with the director. I knock at the door.

Agata Orłowska receives me very warmly. We are going to talk about her mother, Stanisława Dobrowolska – a biology teacher and Pyskowice activist.

Stanisława came to Pyskowice (or rather to the nearby Dzierżoniów to be more precise) in 1961. As a young biology teacher, she arrived with one suitcase and a work order (such were the times). She was very warmly welcomed (she was given a bicycle and sometimes someone left a basket of forest mushrooms at her door). She moved into a rented room, which turned out to be very cold, and then the school headmistress invited Stanisława to her house. Times were hard, but people showed a lot of warmth and kindness to each other. There were too few teachers, different classes were put together and Stanisława had to teach everything. In 1963 she gave birth to a daughter, and this was also the year in which the new school (no. 6 today) was founded. Stanisława was invited to create it. She was a well-liked teacher and had a good rapport with her pupils.

Charismatic, just like the owner of the cult Town Hall (Ratuszowa) Restaurant.

The Pod Ratuszem restaurant on the market square in Pyskowice. Or just Ratuszowa, as the locals call it. I peep through the barred windows. The light, streaming in through the sliding door, lands on white tablecloths. Plastic flowers in vases. Plates arranged in even rows. There is a notice on the wall. The restaurant and shop are closed. We are sorry. Premises for sale.

Jadwiga Żelazna receives me at home. A long table, classical music in the background, delicious coffee and tiramisu in front of me. The hostess – elegant and refined. Always wearing her make-up, her hair tied in a bun, she is charming woman, honest and thrifty… This is how she is remembered by the locals, to whom she seems a bit like a character from an old film. Will she tell me about the social life of Pyskowice in recent decades?

…

After her war wanderings, Helena returned to her beloved Peiskretscham and was buried here. Stanisława Dobrowolska’s granddaughter says: “With grandma, you had to leave an hour earlier because everyone wanted to talk to her, they stopped her in the street, she talked to everyone.” This tale of the charismatic owner of Ratuszowa is accompanied with numerous photos of Pyskowice from the restaurant’s heyday. Plenty of memories.

Everything gets mixed up. Women and men of all ages write to me. My heroines live in the minds of Pyskowice residents. Every herstory has a sequel. These herstorical tropes may not be obvious but they are certainly emotive and engaging. The past comes to life – herstories have power!